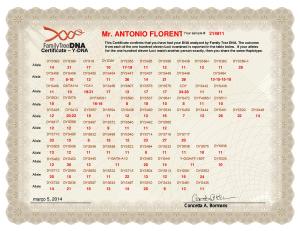

My Father Y-DNA Haplogroup E1b1a7a,100% Tribe Bamileke of Cameroon

MEU PAI HAPLOGROUP Y-DNA E1b1a7a

MEU PAI HAPLOGROUP Y-DNA E1b1a7a

My Father Y-DNA Haplogroup E1b1a7a,100% Tribe Bamileke of Cameroon

My Father Y-DNA Haplogroup E1b1a7a,100% Tribe Bamileke of Cameroon

My Father Y-DNA Haplogroup E1b1a7a,100% Tribe Bamileke of Cameroon

My Father Y-DNA Haplogroup E1b1a7a,100% Tribe Bamileke of Cameroon

Ramesses III

| Ramesses III | |

|---|---|

| Ramses III, Rameses III | |

Relief from the sanctuary of the Temple of Khonsu at Karnak depicting Ramesses III

|

|

| Pharaoh of Egypt | |

| Reign | 1186–1155 BC, 20th Dynasty |

| Predecessor | Setnakhte |

| Successor | Ramesses IV |

| Consort(s) | Iset Ta-Hemdjert, Tyti, Tiye |

| Children | Ramesses IV, Ramesses VI,Ramesses VIII, Amun-her-khepeshef, Meryamun,Pareherwenemef,Khaemwaset, Meryatum,Montuherkhopshef, Pentawere,Duatentopet (?) |

| Father | Setnakhte |

| Mother | Tiy-Merenese |

| Died | 1155 BC |

| Burial | KV11 |

| Monuments | Medinet Habu |

Usimare Ramesses III (also written Ramses and Rameses) was the second Pharaoh of the Twentieth Dynasty and is considered to be the last great New Kingdom king to wield any substantial authority over Egypt.

Ramesses III was the son of Setnakhte and Queen Tiy-Merenese. He was probably murdered by an assassin in a conspiracy led by one of his secondary wives and her minor son.

Contents

[hide]

Name[edit]

Ramesses’ two main names transliterate as wsr-mꜢʿt-rʿ–mry-ỉmn rʿ-ms-s–ḥḳꜢ-ỉwnw. They are normally realised as Usermaatre-meryamun Ramesse-hekaiunu, meaning “Powerful one of Ma’at and Ra, Beloved of Amun, Ra bore him, Ruler of Heliopolis“.

Ascension[edit]

Ramesses III is believed to have reigned from March 1186 to April 1155 BC. This is based on his known accession date of I Shemu day 26 and his death on Year 32 III Shemu day 15, for a reign of 31 years, 1 month and 19 days.[1] Alternate dates for his reign are 1187 to 1156 BC.

In a description of his coronation from Medinet Habu, four doves were said to be “dispatched to the four corners of the horizon to confirm that the living Horus, Ramses III, is (still) in possession of his throne, that the order of Maat prevails in the cosmos and society”.[2][3]

Tenure of constant war[edit]

During his long tenure in the midst of the surrounding political chaos of the Greek Dark Ages, Egypt was beset by foreign invaders (including the so-called Sea Peoples and the Libyans) and experienced the beginnings of increasing economic difficulties and internal strife which would eventually lead to the collapse of the Twentieth Dynasty. In Year 5 of his reign, the Sea Peoples, including Peleset, Denyen, Shardana, Meshwesh of the sea, and Tjekker, invaded Egypt by land and sea. Ramesses III defeated them in two great land and sea battles. Although the Egyptians had a reputation as poor sea men they fought tenaciously. Rameses lined the shores with ranks of archers who kept up a continuous volley of arrows into the enemy ships when they attempted to land on the banks of the Nile. Then the Egyptian navy attacked using grappling hooks to haul in the enemy ships. In the brutal hand to hand fighting which ensued, the Sea People were utterly defeated. The Harris Papyrus state:

As for those who reached my frontier, their seed is not, their heart and their soul are finished forever and ever. As for those who came forward together on the seas, the full flame was in front of them at the Nile mouths, while a stockade of lances surrounded them on the shore, prostrated on the beach, slain, and made into heaps from head to tail.[4]

Ramesses III claims that he incorporated the Sea Peoples as subject peoples and settled them in Southern Canaan, although there is no clear evidence to this effect; the pharaoh, unable to prevent their gradual arrival in Canaan, may have claimed that it was his idea to let them reside in this territory. Their presence in Canaan may have contributed to the formation of new states in this region such as Philistia after the collapse of the Egyptian Empire in Asia. Ramesses III was also compelled to fight invading Libyan tribesmen in two major campaigns in Egypt’s Western Delta in his Year 6 and Year 11 respectively.[5]

Economic turmoil[edit]

The heavy cost of these battles slowly exhausted Egypt’s treasury and contributed to the gradual decline of the Egyptian Empire in Asia. The severity of these difficulties is stressed by the fact that the first known labor strike in recorded history occurred during Year 29 of Ramesses III’s reign, when the food rations for the Egypt’s favoured and elite royal tomb-builders and artisans in the village of Set Maat her imenty Waset (now known as Deir el Medina), could not be provisioned.[6] Something in the air (possibly theHekla 3 eruption) prevented much sunlight from reaching the ground and also arrested global tree growth for almost two full decades until 1140 BC. The result in Egypt was a substantial inflation in grain prices under the later reigns of Ramesses VI–VII, whereas the prices for fowl and slaves remained constant.[7] Thus the cooldown affected Ramesses III’s final years and impaired his ability to provide a constant supply of grain rations to the workman of the Deir el-Medina community.

These difficult realities are completely ignored in Ramesses’ official monuments, many of which seek to emulate those of his famous predecessor, Ramesses II, and which present an image of continuity and stability. He built important additions to the temples at Luxor andKarnak, and his funerary temple and administrative complex at Medinet-Habu is amongst the largest and best-preserved in Egypt; however, the uncertainty of Ramesses’ times is apparent from the massive fortifications which were built to enclose the latter. No Egyptian temple in the heart of Egypt prior to Ramesses’ reign had ever needed to be protected in such a manner.

Conspiracy and death[edit]

Thanks to the discovery of papyrus trial transcripts (dated to Ramesses III), it is now known that there was a plot against his life as a result of a royal harem conspiracy during a celebration at Medinet Habu. The conspiracy was instigated by Tiye, one of his three known wives (the others being Tyti and Iset Ta-Hemdjert), over whose son would inherit the throne. Tyti’s son, Ramesses Amonhirkhopshef (the futureRamesses IV), was the eldest and the successor chosen by Ramesses III in preference to Tiye’s son Pentaweret.

The trial documents[8] show that many individuals were implicated in the plot.[9] Chief among them were Queen Tiye and her sonPentaweret, Ramesses’ chief of the chamber, Pebekkamen, seven royal butlers (a respectable state office), two Treasury overseers, two Army standard bearers, two royal scribes and a herald. There is little doubt that all of the main conspirators were executed: some of the condemned were given the option of committing suicide (possibly by poison) rather than being put to death.[10] According to the surviving trials transcripts, 3 separate trials were started in total while 38 people were sentenced to death.[11] The tombs of Tiye and her son Pentaweret were robbed and their names erased to prevent them from enjoying an afterlife. The Egyptians did such a thorough job of this that the only references to them are the trial documents and what remains of their tombs.

Some of the accused harem women tried to seduce the members of the judiciary who tried them but were caught in the act. Judges who were involved were severely punished.[12]

It is not certain whether the assassination plot succeeded since Ramesses IV, the king’s designated successor, assumed the throne upon his death rather than Pentaweret who was intended to be the main beneficiary of the palace conspiracy. Moreover, Ramesses III died in his 32nd year before the summaries of the sentences were composed,[13] but the same year that the trial documents[8]record the trial and execution of the conspirators.

Although it was long believed that Ramesses III’s body showed no obvious wounds,[12] a recent examination of the mummy by a German forensic team, televised in the documentary Ramesses: Mummy King Mystery on the Science Channel in 2011, showed excessive bandages around the neck. A subsequent CT scan that was done in Egypt by Ashraf Selim and Sahar Saleem, professors of Radiology in Cairo University, revealed that beneath the bandages was a deep knife wound across the throat, deep enough to reach the vertebrae. According to the documentary narrator, “It was a wound no one could have survived.”[14] The December 2012 issue of the British Medical Journal quotes the conclusion of the study of the team of researchers, led by Dr Zahi Hawass, the former head of the Egyptian Supreme Council of Antiquity, and his Egyptian team, as well as Dr Albert Zink from the Institute for Mummies and the Iceman of the European Academy of Bolzano/Bozen in Italy, which stated that conspirators murdered pharaoh Ramesses III by cutting his throat.[14][15][16] Zink observes in an interview that:

- “The cut [to Ramesses III’s throat] is…very deep and quite large, it really goes down almost down to the bone (spine) – it must have been a lethal injury.”[17]

Before this discovery it had been speculated that Ramesses III had been killed by means that would not have left a mark on the body. Among the conspirators were practitioners of magic,[18] who might well have used poison. Some had put forth a hypothesis that a snakebite from a viper was the cause of the king’s death. His mummy includes an amulet to protect Ramesses III in the afterlife from snakes. The servant in charge of his food and drink were also among the listed conspirators, but there were also other conspirators who were called the snake and the lord of snakes.

In one respect the conspirators certainly failed. The crown passed to the king’s designated successor: Ramesses IV. Ramesses III may have been doubtful as to the latter’s chances of succeeding him, given that, in the Great Harris Papyrus, he implored Amun to ensure his son’s rights.[19]

Legacy[edit]

The Great Harris Papyrus or Papyrus Harris I, which was commissioned by his son and chosen successor Ramesses IV, chronicles this king’s vast donations of land, gold statues and monumental construction to Egypt’s various temples at Piramesse, Heliopolis, Memphis, Athribis, Hermopolis, This, Abydos, Coptos, El Kab and other cities in Nubia and Syria. It also records that the king dispatched a trading expedition to the Land of Punt and quarried the copper mines of Timna in southern Canaan. Papyrus Harris I records some of Ramesses III activities:

“I sent my emissaries to the land of Atika, [ie: Timna] to the great copper mines which are there. Their ships carried them along and others went overland on their donkeys. It had not been heard of since the (time of any earlier) king. Their mines were found and (they) yielded copper which was loaded by tens of thousands into their ships, they being sent in their care to Egypt, and arriving safely.” (P. Harris I, 78, 1-4)[20]

More notably, Ramesses began the reconstruction of the Temple of Khonsu at Karnak from the foundations of an earlier temple ofAmenhotep III and completed the Temple of Medinet Habu around his Year 12.[21] He decorated the walls of his Medinet Habu temple with scenes of his Naval and Land battles against the Sea Peoples. This monument stands today as one of the best-preserved temples of the New Kingdom.[22]

The mummy of Ramesses III was discovered by antiquarians in 1886 and is regarded as the prototypical Egyptian Mummy in numerous Hollywood movies.[23] His tomb (KV11) is one of the largest in the Valley of the Kings.

Chronological dispute[edit]

Some scientists have tried to establish a chronological point for this pharaoh’s reign at 1159 BC, based on a 1999 dating of the “Hekla 3 eruption” of the Hekla volcano in Iceland. Since contemporary records show that the king experienced difficulties provisioning his workmen at Deir el-Medina with supplies in his 29th Year, this dating of Hekla 3 might connect his 28th or 29th regnal year to c. 1159 BC.[24] A minor discrepancy of 1 year is possible since Egypt’s granaries could have had reserves to cope with at least a single bad year of crop harvests following the onset of the disaster. This implies that the king’s reign would have ended just 3 to 4 years later around 1156 or 1155 BC. A rival date of “2900 BP” or c.1000 BC has since been proposed by scientists based on a re-examination of the volcanic layer.[25] However, no Egyptologist dates Ramesses III’s reign to as late as 1000 BC.

Ancient Genetics[edit]

According to a genetic study in December 2012, Ramesses III belonged to Y-DNA haplogroup E1b1a with an East Africa Origin, a YDNA haplogroup that predominates in most Sub-Saharan Africans.[26]

-

A painted ceiling ofNekhbet at Ramesses III’s mortuary temple at Medinet Habu.

References[edit]

- Jump up^ E.F. Wente & C.C. Van Siclen, “A Chronology of the New Kingdom” in Studies in Honor of George R. Hughes, (SAOC 39) 1976, p.235, ISBN 0-918986-01-X

- Jump up^ Murnane, W. J., United with Eternity: A Concise Guide to the Monuments of Medinet Habu, p. 38, Oriental Institute, Chicago / American University in Cairo Press, 1980.

- Jump up^ Wilfred G. Lambert; A. R. George; Irving L. Finkel (2000). Wisdom, Gods and Literature: Studies in Assyriology in Honour of W.G. Lambert. Eisenbrauns. pp. 384–. ISBN 978-1-57506-004-0. Retrieved 18 August 2012.

- Jump up^ Hasel, Michael G. “Merenptah’s Inscription and Reliefs and the Origin of Israel” in The Near East in the Southwest: Essays in Honor of William G. Dever” edited by Beth Albprt HakhaiThe Annual of the American Schools of Oriental Research Vol. 58 2003, quoting from Edgerton, W. F., and Wilson, John A. 1936 Historical Records of Ramses III, the Texts in Medinet Habu, Volumes I and II. Studies in Ancient Oriental Civilization 12. Chicago: The Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago.

- Jump up^ Nicolas Grimal, A History of Ancient Egypt, Blackwell Books, 1992. p.271

- Jump up^ William F. Edgerton, The Strikes in Ramses III’s Twenty-Ninth Year, JNES 10, No. 3 (July 1951), pp. 137-145

- Jump up^ Frank J. Yurco, p.456

- ^ Jump up to:a b J. H. Breasted, Ancient Records of Egypt, Part Four, §§423-456

- Jump up^ James H. Breasted, Ancient Records of Egypt, Part Four, §§416-417

- Jump up^ James H. Breasted, Ancient Records of Egypt, Part Four, §§446-450

- Jump up^ Joyce Tyldesley, Chronicle of the Queens of Egypt, Thames & Hudson October 2006, p.170

- ^ Jump up to:a b Cambridge Ancient History, Cambridge University Press 2000, p.247

- Jump up^ J. H. Breasted, Ancient Records of Egypt, p.418

- ^ Jump up to:a b See also King Ramesses III’s throat was slit, analysis reveals. Retrieved 2012-12-18.

- Jump up^ British Medical Journal, Study reveals that Pharaoh’s throat was cut during royal coup, Monday, December 17, 2012

- Jump up^ Hawass, Ismail, Selim, Saleem, Fathalla, Waset, Gad, Saad, Fares, Amer, Gostner, Gad, Pusch, Zink (December 17, 2012). “Revisiting the harem conspiracy and death of Ramesses III: anthropological, forensic, radiological, and genetic study”. British Medical Journal 2012 Christmas 2012. Retrieved December 19, 2012.

- Jump up^ AFP (December 18, 2012). “Pharaoh’s murder riddle solved after 3,000 years”. The Daily Telegraph . Retrieved December 18, 2012.

- Jump up^ J. H. Breasted, Ancient Records of Egypt, pp.454-456

- Jump up^ J. H. Breasted, Ancient Records of Egypt, Part Four, §246

- Jump up^ A. J. Peden, The Reign of Ramesses IV, Aris & Phillips Ltd, 1994. p.32 Atika has long been equated with Timna, see here B. Rothenburg, Timna, Valley of the Biblical Copper Mines(1972), pp.201-203 where he also notes the probable port at Jezirat al-Faroun.

- Jump up^ Jacobus Van Dijk, ‘The Amarna Period and the later New Kingdom’ in The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt, ed. Ian Shaw, Oxford University Press paperback, (2002) p.305

- Jump up^ Van Dijk, p.305

- Jump up^ Bob Brier, The Encyclopedia of Mummies, Checkmark Books, 1998., p.154

- Jump up^ Frank J. Yurco, “End of the Late Bronze Age and Other Crisis Periods: A Volcanic Cause” in Gold of Praise: Studies on Ancient Egypt in Honor of Edward F. Wente, ed: Emily Teeter & John Larson, (SAOC 58) 1999, pp.456-458

- Jump up^ At first, scholars tried to redate the event to “3000 BP”: TOWARDS A HOLOCENE TEPHROCHRONOLOGY FOR SWEDEN, Stefan Wastegǎrd, XVI INQUA Congress, Paper No. 41-13, Saturday, July 26, 2003. Also: Late Holocene solifluction history reconstructed using tephrochronology, Martin P. Kirkbride & Andrew J. Dugmore, Geological Society, London, Special Publications; 2005; v. 242; p. 145-155.

- Jump up^ Hawass at al. 2012, Revisiting the harem conspiracy and death of Ramesses III: anthropological, forensic, radiological, and genetic study. BMJ2012;345doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmj.e8268 Published 17 December 2012

Further reading[edit]

- Eric H. Cline and David O’Connor, eds. Ramesses III: The Life and Times of Egypt’s Last Hero (University of Michigan Press; 2012) 560 pages; essays by scholars

External links[edit]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Ramses III. |

|

||

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bamileke_people

Bamileke people

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

“Bazu” redirects here. For the Romanian aviator, see Constantin Cantacuzino.

“Bazu” was also the name of an ancient country in Southwest Asia.

Bamileke dancers in Batié, West Province

Bamileke tamtam

The Bamileke is the ethnic group which is now dominant in Cameroon’s West and Northwest Provinces. It is part of the Semi-Bantu (or Grassfields Bantu) ethnic group. The Bamileke are regrouped under several groups, each under the guidance of a chief or fon. Nonetheless, all of these groups have the same ancestors and thus share the same history, culture, and languages. The Bamileke have a population of over 3,500,000 individuals. They speak a number of related languages from the Bantoid branch of the Niger–Congo language family. These languages are closely related, however, and some classifications identify a Bamileke dialect continuum with seventeen or more dialects.

Contents

[hide]

- 1 Organization

- 2 Languages

- 3 History

- 4 Lifestyle and settlement patterns

- 5 References

- 6 Further reading

- 7 External links

Organization[edit]

The Bamileke are organized under several chiefdom (or fondom). Of these, the fondoms of Bafang, Bafoussam, Bandjoun, Bangangté, Bawaju,Dschang, and Mbouda are the most prominent. The Bamileke also share much history and culture with the neighbouring fondoms of the Northwest province and notably the Lebialem region of the Southwest province, but the groups have been divided since their territories were split between the French and English in colonial times.

Languages[edit]

Main article: Bamileke languages

Following Ethnologue classification, we can identify 11 different languages or dialects:

Variants of Ghomala’ are spoken in most of the Mifi, Koung-Khi, Hauts-Plateaux departments, the eastern Menoua, and portions of Bamboutos, by 260,000 people (1982, SIL). The main fondoms are Baham, Bafoussam, Bamendjou, Bandjoun.

Towards southwest is spoken Fe’fe’ in the Upper Nkam division. The main towns include Bafang, Baku, and Kékem.

Nda’nda’ occupy the western third of the Ndé division. The major settlement is at Bazou.

Yemba is spoken by 300,000 or more people in 1992. Their lands span most of the Menoua division to the west of the Bandjoun, with their capital at Dschang. Fokoué is another major settlement.

Medumba is spoken in most of the Ndé division, by 210,000 people in 1991, with major settlements at Bangangte and Tonga.

Mengaka, Ngiemboon, Ngomba and Ngombale are spoken in Mbouda.

Kwa is spoken between the Ndé and the Littoral province, Ngwe around Fontem in the Southwest province.

Bamileke belongs to the Mbam-Nkam group of Grassfields languages, whose attachment to the Bantu division is still disputed. While some consider it a Bantu or semi-Bantu language, others prefer to include Bamileke in the Niger-Congo group. Bamileke is not a unique language. It seems that Bamileke Medumba stems from Ancient Egyptian and is the root language for many other Bamileke variants.

History[edit]

Main source: “Histoire et anthropologie du peuple bamiléké” (Paris: l’Harmattan, 2010, 242p.), by Dieudonné Toukam.ISBN : 978-2-296-11827-0

The Bamileke are the native people three regions of Cameroon, namely West, North-West and South-West. Though greater part of this people are from the West region, it is estimated that over the 1/3 of Bamileke are from the English speaking regions, the majority of which are from the North-West region (there are 123 Bamileke villages in this region, against 06 in the South-West). The Grassfields area therefore encompasses the West and North-West and small part of the South-West region of Cameroon. Apart from the Bamileke, there are other tribes that are historically more or less linked to the Bamileke, such as the Igbo’s of Nigeria whether by blood or through certain cultural intercourse, (D. Toukam, “Histoire et anthropologie du peuple bamiléké”, p. 15).

The Bamileke speak a semi-Bantu language and are related to Bantu peoples. Historically, the Bamun and the Bamileke were united. The founder of this group (Nchare) was the younger brother of the founder of Bafoussam. Bamiléké are a group comprising many tribes. In this group, there are at least eight different cultures, including Dschang, Bafang, Bagangté, Mbouda and Bafoussam.

During the mid-17th century, the Bamiléké people’s forefathers left the North to avoid being forced to convert to Islam. They migrated as far south as Foumban. Conquerors came all the way to Foumban to try to impose Islam on them. A war began, pushing some people to leave while others remained, submitting to Islam. This marks the division between the Bamun and Bamiléké people.

Bantu refers to a large, complex linguistic grouping of peoples in Africa. The Cameroon-Bamileke Bantu people cluster encompasses multiple Bantu ethnic groups primarily found in Cameroon, the largest of which is the Bamileke. The Bamileke, whose origins trace to Egypt, migrated to what is now northern Cameroon between the 11th and 14th centuries. In the 17th century they migrated further south and west to avoid being forced to convert to Islam. Today, a majority of peoples within this people cluster are Christians.

German administration[edit]

Germany gained control of “Kamerun” in 1884.

The Germans first applied the term “Bamileke” to the people as administrative shorthand for the people of the region.

French administration and post-independence[edit]

The Bamileke are very dynamic and have a great sense of entrepreneurship. Thus, they can be found in almost all provinces of Cameroon and in the world, mainly as business owner.

In 1955, the colonial French power banned the Union des Populations du Cameroun (UPC) political party, which was claiming the independence of Cameroon. Following that, the French started an offensive against UPC militants. Part of the attacks were done in the West province, region of the Bamileke (Some people considered those attacks as a genocide, given the high number of people killed).[1]

Lifestyle and settlement patterns[edit]

Political structure and agriculture[edit]

Statue of a chief at Bana.

The Bamileke’s settlements follow a well organized and structured pattern. Houses of family members are often grouped together, often surrounded by small fields. Men typically clear the fields, but it is largely women who work them. Most work is done with tools such as machetes and hoes. Staple crops include cocoyams, groundnuts and maize.

Bamileke settlement are organized as chiefdoms. The chief, or fon or fong is considered as the spiritual, political, judicial and military leader. The Chief is also considered as the ‘Father’ of the chiefdom. He thus has great respect from the population. The successor of the ‘Father’ is chosen among his children. The successor’s identity is typically kept secret until the fon’s death.

The fon has typically 9 ministers and several other advisers and councils. The ministers are in charge of the crowning of the new fon. The council of ministers, also known as the Council of Notables is called Kamveu. In addition, a “queen mother” or mafo was an important figure for some fons in the past. Below the fon and his advisers lie a number of ward heads, each responsible for a particular portion of the village. Some Bamileke groups also recognise sub-chiefs, or fonte.

Economic activities[edit]

Hut at the chefferie of Bana.

The Bamileke are renowned for their skilled craftsmen and great sense of business. Their artwork is highly praised, though since the colonial period, many traditional arts and crafts have been abandoned. Bamileke are particularly celebrated carvers in wood, ivory, and horn. Chief’s compounds are notable for their intricately carved doorframes and columns.

Traditional homes are constructed by first erecting a raffia-pole frame into four square walls. Builders then stuff the resulting holes with grass and cover the whole building with mud. The thatched roof is typically shaped into a tall cone. Nowadays, however, this type of construction is mostly reserved for barns, storage buildings, and gathering places for various traditional secret societies. Instead, modern Bamileke homes are made of bricks of either sun-dried mud or of concrete. Roofs are of metal sheeting.

Bamileke have some of Cameroon’s most prominent entrepreneurs. Bamileke are also found in all other professional areas as artisans, farmers, traders, and skilled professionals. They thus play an important role in the economic development of Cameroon.

Religious beliefs[edit]

During the colonial period, parts of the Bamileke adopted Christianity. Some of them practice Islam toward the border with the Adamawa Tikar and the Bamun. The Bamileke have worn elephant mask for dance ceremonies or funerals.[citation needed]

Succession and kinship patterns[edit]

The Bamileke trace ancestry, inheritance and succession through the male line, and children belong to the fondom of their father. After a man’s death, all of his possessions typically go to a single, male heir. Polygamy (more specifically, polygyny) is practiced, and some important individuals may have literally hundreds of wives. Marriages typically involve a bride price to be paid to the bride’s family.

It is argued that the Bamileke inheritance customs contributed to their success in the modern world:

“Succession and inheritance rules are determined by the principle of patrilineal descent. According to custom, the eldest son is the probable heir, but a father may choose any one of his sons to succeed him. An heir takes his dead father’s name and inherits any titles held by the latter, including the right to membership in any societies to which he belonged. And, until the mid-1960s, when the law governing polygamy was changed, the heir also inherited his father’s wives–a considerable economic responsibility. The rights in land held by the deceased were conferred upon the heir subject to the approval of the chief, and, in the event of financial inheritance, the heir was not obliged to share this with other family members. The ramifications of this are significant. First, dispossessed family members were not automatically entitled to live off the wealth of the heir. Siblings who did not share in the inheritance were, therefore, strongly encouraged to make it on their own through individual initiative and by assuming responsibility for earning their livelihood. Second, this practice of individual responsibility in contrast to a system of strong family obligations prevented a drain on individual financial resources. Rather than spend all of the inheritance maintaining unproductive family members, the heir could, in the contemporary period, utilize his resources in more financially productive ways such as for savings and investment. […] Finally, the system of inheritance, along with the large-scale migration resulting from population density and land pressures, is one of the internal incentives that accounts for Bamileke success in the nontraditional world”.[2]

Donald L. Horowitz also attributes the economic success of the Bamileke to their inheritance customs, arguing that it encouraged younger sons to seek their own living abroad. He wrote in “Ethnic groups in conflict”: “Primogeniture among the Bamileke and matrilineal inheritance among the Minangkabau of Indonesia have contributed powerfully to the propensity of males from both groups to migrate out of their home region in search of opportunity”.[3]

References[edit]

- Jump up^ Owono, Julie (25 January 2012). “Unspoken history: The last genocide of the 20th century”. Al Jazeera. Retrieved 26 January 2012.

- Jump up^ A.I.D. Evaluation Special Study No. 15 THE PRIVATE SECTOR: – Individual Initiative, And Economic Growth In An African Plural Society The Bamileke Of Cameroonhttp://pdf.usaid.gov/pdf_docs/pnaal016.pdf

- Jump up^ http://books.google.es/books?id=Q82saX1HVQYC&pg=PA155&lpg=PA155&dq=%22Primogeniture%22+%22Bamileke%22&source=bl&ots=JMOOcssnc-&sig=BtkVUJrmKPp6ZW48t5fyMx_X4Ak&hl=es&sa=X&ei=UgeLUuChHMSv7AbwnYCYBw&ved=0CEQQ6AEwAg#v=onepage&q=%22Primogeniture%22%20%22Bamileke%22&f=false

- Toukam, Dieudonné (2010), Histoire et anthropologie du peuple bamiléké, Paris: l’Harmattan, 2010, 242p.

- Toukam, Dieudonné (2008), Parlons bamiléké. Langue et culture de Bafoussam, Paris: L’Harmattan, 255p.

- Fanso, V.G. (1989) Cameroon History for Secondary Schools and Colleges, Vol. 1: From Prehistoric Times to the Nineteenth Century. Hong Kong: Macmillan Education Ltd, 1989.

- Neba, Aaron, Ph.D. (1999) Modern Geography of the Republic of Cameroon, 3rd ed. Bamenda: Neba Publishers, 1999.

- Ngoh, Victor Julius (1996) History of Cameroon Since 1800. Limbé: Presbook, 1996.

Further reading[edit]

- Knöpfli, Hans (1997—2002) Crafts and Technologies: Some Traditional Craftsmen and Women of the Western Grassfields of Cameroon. 4 vols. Basel, Switzerland: Basel Mission.

External links[edit]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Bamileke. |

http://www.shavei.org/category/communities/other_communities/africa/cameroon/?lang=en

Cameroon

There are some who believe that an ancient Jewish presence may have at one time existed in Cameroon via merchants who arrived from Egypt for trade. According to these accounts, the early communities in Cameroon observed rituals such as separation of dairy and meat products, as well as wearingtefillin.

There are also claims that Jews migrated into Cameroon much later, after being forced southward due to the Islamic conquests of North Africa.

The main claims of a Jewish presence in Cameroon are made by Rabbi Yisrael Oriel, formerly known as Bodol Ngimbus-Ngimbus. He was born into the Ba-Saa tribe; the word “Ba-Saa,” he says, is from the Hebrew for “on a journey.” Oriel also claims to be a Levite descended from Moses.

According to Oriel in 1920 there were 400,000 “Israelites” in Cameroon, but by 1962 the number had decreased to 167,000 due to conversions to Christianity and Islam. He admitted that these tribes had not been accepted according to Jewish law, although he claimed that he could still prove their Jewish status from medieval rabbinic sources.

A website called “Jewish Cameroon” provides more details. Oriel describes the period between 1920 and 1962 as “a ‘spiritual Shoah.’ Because of intense missionary activity, it was like the Soviet Union where Jews had no permission for Jewish education, no batei din (Jewish courts), synagogues or sifrei (books of the) Torah. Everything was taught by oral tradition, Oriel says.”

Oriel’s father, the website continues, Hassid Peniel Moshe Shlomo (Ngimbus Nemb Yemba) was a textile manufacturer, scribe, mohel (ritual circumciser) and tribal leader. Oriel says his father was imprisoned 50 times for teaching his traditional Jewish beliefs. In 1932 he ran away from a Catholic school because they had wanted him to train for the priesthood.

Oriel’s grandfather reportedly built a synagogue in Cameroon, but that it is now in ruins. Oriel’s grandfather is said to have been the last gabbai of the synagogue.

Oriel’s mother, who he calls Orah Leah (her given name was Ngo Ngog Lum), had a large kitchen in which milk and meat were separated – by six meters, he says. Shortly before his mother died in 1957, she told him: “My beloved child, one day you will go to ‘Yesulmi’.” It was not till 1980 that he realized that she must have meant Jerusalem.

Oriel left Cameroon in the early 1960s after the country received independence. He studied law and international relations in France.

Oriel formally converted to Judaism some 20 years and was ordained as a rabbi in Israel, to which he made aliyah and where he lived briefly. He now resides in London and prays at the Persian Hebrew congregation and the Moroccan “Hida” Synagogue and Bekt Midrash on East Bank, Stamford Hill, London. You can see a photo of Oriel here.

Oriel remains active in trying to bring Judaism to Cameroon, as well as neighboring Nigeria, and to bring what he claims are “the 10 lost tribes” back to the fold. There is much more about Oriel on the Jewish Cameroonsite, including some more outlandish claims and grievances Oriel has against the established Jewish community.

Other reported Jewish tribes in Cameroon are said to include Haussa, descended from the tribe of Issachar, who were forced to convert to Islam in the eighth and ninth centuries, and the Bamileke who are largely Christian today. Nchinda Gideon claims that these early immigrants built synagogues but there are no records of them in Cameroon today.

American actor Yaphet Kotto, whose parents emigrated from Cameroon to the United States, claims Jewish descent. Kotto, who died in 2008, had a starring role in the television series Homicide: Life on the Streetand also appeared in films such as Alien and the James Bond movie Live and Let Die.

In his autobiography entitled Royalty, Kotto writes that his father was “the crown prince of Cameroon” and that he was an observant Jew who spoke Hebrew. Kotto’s mother reportedly converted to Judaism before marrying his father. Kotto also says that his great-grandfather, King Alexander Bell, ruled the Douala region of Cameroon in the late 19th century and was also a practicing Jew.

Kotto says that his paternal family originated from Israel and migrated to Egypt and then Cameroon, and have been African Jews for many generations. Kotto writes that being black and Jewish gave other children even more reason to pick on him growing up in New York City. He says that he went to synagogue and occasionally wore a yarmulke when he was younger.

A very tenuous, primarily linguistic connection between Cameroon and ancient Israel can be found through another tribe known as the Bankon who live in the Littoral region of Cameroon. The word “Ban” – also pronounced “Kon” – means “son of prince” in Assyrian, an Aramaic dialect. In her work The Negro-African Languages, a French scholar, Lilias Homburger, points out that the Bankon’s language is “Kum” which may derive from the Hebrew for “arise” or “get up!” Further, the Assyrians called the House of Israel by the name of Kumri.

More recent Jewish presence in Cameroon

Twelve years ago, 1,000 Evangelical Christians in Cameroon decided they no longer wanted to practice Christianity and turned instead to Judaism, embracingpractices from the bible. Their informal conversion to Judaism is similar to Uganda’sAbuyadaya Jewish community which, in 1919, also moved towards Judaism even though, in both cases, they had never met any Jews and had no in-person guidance or mentoring in developing their Jewish identity. The Cameroon community calls itself Beth Yeshourun and is very small, with only 60 members in total.

Much of what the community has learned has been via the Internet, including downloading prayers and songs. Some of the community has taught itself Hebrew; others pray in a mixture of French and transliterated Hebrew.

Rabbis Bonita and Gerald Sussman visited the community in 2010. Their description is presented in detail on the Kulanu website. Here are a few highlights from that trip.

- The Sussmans chose to trust the community’s level of kashrut, eating primarily fish and vegetables.

- Community members washed their hands ritually before eating bread and a meal.

- The community was fairly knowledgeable about Jewish tradition and asked the Sussman’s many questions about Jewish law, such as what to eat at a family event that is not kosher, when do you pray the Minchaafternoon service when you are traveling, and must you stand during the Amidah prayers if you are sick?

- The Shabbat service, held in the Beth Yeshourun synagogue, was remarkable similar to today’s mainstream Orthodox Judaism, including the full Kabbalat Shabbat, the singing of Lecha Dodi and even the closing Yigdal prayer.

- On Shabbat day, the community sang a mixture of songs in the local language as well as modern Israeli songs such as Jerusalem of Gold.

- The community prays three times a day and holds Torah study sessions twice a week, using material gleaned from the web.

- The community has created its own siddur (prayer book) of 150 pages, also by downloading content from the Internet.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bamileke_people

Bamileke people

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

“Bazu” redirects here. For the Romanian aviator, see Constantin Cantacuzino.

“Bazu” was also the name of an ancient country in Southwest Asia.

Bamileke dancers in Batié, West Province

Bamileke tamtam

The Bamileke is the ethnic group which is now dominant in Cameroon’s West and Northwest Provinces. It is part of the Semi-Bantu (or Grassfields Bantu) ethnic group. The Bamileke are regrouped under several groups, each under the guidance of a chief or fon. Nonetheless, all of these groups have the same ancestors and thus share the same history, culture, and languages. The Bamileke have a population of over 3,500,000 individuals. They speak a number of related languages from the Bantoid branch of the Niger–Congo language family. These languages are closely related, however, and some classifications identify a Bamileke dialect continuum with seventeen or more dialects.

Contents

[hide]

- 1 Organization

- 2 Languages

- 3 History

- 4 Lifestyle and settlement patterns

- 5 References

- 6 Further reading

- 7 External links

Organization[edit]

The Bamileke are organized under several chiefdom (or fondom). Of these, the fondoms of Bafang, Bafoussam, Bandjoun, Bangangté, Bawaju,Dschang, and Mbouda are the most prominent. The Bamileke also share much history and culture with the neighbouring fondoms of the Northwest province and notably the Lebialem region of the Southwest province, but the groups have been divided since their territories were split between the French and English in colonial times.

Languages[edit]

Main article: Bamileke languages

Following Ethnologue classification, we can identify 11 different languages or dialects:

Variants of Ghomala’ are spoken in most of the Mifi, Koung-Khi, Hauts-Plateaux departments, the eastern Menoua, and portions of Bamboutos, by 260,000 people (1982, SIL). The main fondoms are Baham, Bafoussam, Bamendjou, Bandjoun.

Towards southwest is spoken Fe’fe’ in the Upper Nkam division. The main towns include Bafang, Baku, and Kékem.

Nda’nda’ occupy the western third of the Ndé division. The major settlement is at Bazou.

Yemba is spoken by 300,000 or more people in 1992. Their lands span most of the Menoua division to the west of the Bandjoun, with their capital at Dschang. Fokoué is another major settlement.

Medumba is spoken in most of the Ndé division, by 210,000 people in 1991, with major settlements at Bangangte and Tonga.

Mengaka, Ngiemboon, Ngomba and Ngombale are spoken in Mbouda.

Kwa is spoken between the Ndé and the Littoral province, Ngwe around Fontem in the Southwest province.

Bamileke belongs to the Mbam-Nkam group of Grassfields languages, whose attachment to the Bantu division is still disputed. While some consider it a Bantu or semi-Bantu language, others prefer to include Bamileke in the Niger-Congo group. Bamileke is not a unique language. It seems that Bamileke Medumba stems from Ancient Egyptian and is the root language for many other Bamileke variants.

History[edit]

Main source: “Histoire et anthropologie du peuple bamiléké” (Paris: l’Harmattan, 2010, 242p.), by Dieudonné Toukam.ISBN : 978-2-296-11827-0

The Bamileke are the native people three regions of Cameroon, namely West, North-West and South-West. Though greater part of this people are from the West region, it is estimated that over the 1/3 of Bamileke are from the English speaking regions, the majority of which are from the North-West region (there are 123 Bamileke villages in this region, against 06 in the South-West). The Grassfields area therefore encompasses the West and North-West and small part of the South-West region of Cameroon. Apart from the Bamileke, there are other tribes that are historically more or less linked to the Bamileke, such as the Igbo’s of Nigeria whether by blood or through certain cultural intercourse, (D. Toukam, “Histoire et anthropologie du peuple bamiléké”, p. 15).

The Bamileke speak a semi-Bantu language and are related to Bantu peoples. Historically, the Bamun and the Bamileke were united. The founder of this group (Nchare) was the younger brother of the founder of Bafoussam. Bamiléké are a group comprising many tribes. In this group, there are at least eight different cultures, including Dschang, Bafang, Bagangté, Mbouda and Bafoussam.

During the mid-17th century, the Bamiléké people’s forefathers left the North to avoid being forced to convert to Islam. They migrated as far south as Foumban. Conquerors came all the way to Foumban to try to impose Islam on them. A war began, pushing some people to leave while others remained, submitting to Islam. This marks the division between the Bamun and Bamiléké people.

Bantu refers to a large, complex linguistic grouping of peoples in Africa. The Cameroon-Bamileke Bantu people cluster encompasses multiple Bantu ethnic groups primarily found in Cameroon, the largest of which is the Bamileke. The Bamileke, whose origins trace to Egypt, migrated to what is now northern Cameroon between the 11th and 14th centuries. In the 17th century they migrated further south and west to avoid being forced to convert to Islam. Today, a majority of peoples within this people cluster are Christians.

German administration[edit]

Germany gained control of “Kamerun” in 1884.

The Germans first applied the term “Bamileke” to the people as administrative shorthand for the people of the region.

French administration and post-independence[edit]

The Bamileke are very dynamic and have a great sense of entrepreneurship. Thus, they can be found in almost all provinces of Cameroon and in the world, mainly as business owner.

In 1955, the colonial French power banned the Union des Populations du Cameroun (UPC) political party, which was claiming the independence of Cameroon. Following that, the French started an offensive against UPC militants. Part of the attacks were done in the West province, region of the Bamileke (Some people considered those attacks as a genocide, given the high number of people killed).[1]

Lifestyle and settlement patterns[edit]

Political structure and agriculture[edit]

Statue of a chief at Bana.

The Bamileke’s settlements follow a well organized and structured pattern. Houses of family members are often grouped together, often surrounded by small fields. Men typically clear the fields, but it is largely women who work them. Most work is done with tools such as machetes and hoes. Staple crops include cocoyams, groundnuts and maize.

Bamileke settlement are organized as chiefdoms. The chief, or fon or fong is considered as the spiritual, political, judicial and military leader. The Chief is also considered as the ‘Father’ of the chiefdom. He thus has great respect from the population. The successor of the ‘Father’ is chosen among his children. The successor’s identity is typically kept secret until the fon’s death.

The fon has typically 9 ministers and several other advisers and councils. The ministers are in charge of the crowning of the new fon. The council of ministers, also known as the Council of Notables is called Kamveu. In addition, a “queen mother” or mafo was an important figure for some fons in the past. Below the fon and his advisers lie a number of ward heads, each responsible for a particular portion of the village. Some Bamileke groups also recognise sub-chiefs, or fonte.

Economic activities[edit]

Hut at the chefferie of Bana.

The Bamileke are renowned for their skilled craftsmen and great sense of business. Their artwork is highly praised, though since the colonial period, many traditional arts and crafts have been abandoned. Bamileke are particularly celebrated carvers in wood, ivory, and horn. Chief’s compounds are notable for their intricately carved doorframes and columns.

Traditional homes are constructed by first erecting a raffia-pole frame into four square walls. Builders then stuff the resulting holes with grass and cover the whole building with mud. The thatched roof is typically shaped into a tall cone. Nowadays, however, this type of construction is mostly reserved for barns, storage buildings, and gathering places for various traditional secret societies. Instead, modern Bamileke homes are made of bricks of either sun-dried mud or of concrete. Roofs are of metal sheeting.

Bamileke have some of Cameroon’s most prominent entrepreneurs. Bamileke are also found in all other professional areas as artisans, farmers, traders, and skilled professionals. They thus play an important role in the economic development of Cameroon.

Religious beliefs[edit]

During the colonial period, parts of the Bamileke adopted Christianity. Some of them practice Islam toward the border with the Adamawa Tikar and the Bamun. The Bamileke have worn elephant mask for dance ceremonies or funerals.[citation needed]

Succession and kinship patterns[edit]

The Bamileke trace ancestry, inheritance and succession through the male line, and children belong to the fondom of their father. After a man’s death, all of his possessions typically go to a single, male heir. Polygamy (more specifically, polygyny) is practiced, and some important individuals may have literally hundreds of wives. Marriages typically involve a bride price to be paid to the bride’s family.

It is argued that the Bamileke inheritance customs contributed to their success in the modern world:

“Succession and inheritance rules are determined by the principle of patrilineal descent. According to custom, the eldest son is the probable heir, but a father may choose any one of his sons to succeed him. An heir takes his dead father’s name and inherits any titles held by the latter, including the right to membership in any societies to which he belonged. And, until the mid-1960s, when the law governing polygamy was changed, the heir also inherited his father’s wives–a considerable economic responsibility. The rights in land held by the deceased were conferred upon the heir subject to the approval of the chief, and, in the event of financial inheritance, the heir was not obliged to share this with other family members. The ramifications of this are significant. First, dispossessed family members were not automatically entitled to live off the wealth of the heir. Siblings who did not share in the inheritance were, therefore, strongly encouraged to make it on their own through individual initiative and by assuming responsibility for earning their livelihood. Second, this practice of individual responsibility in contrast to a system of strong family obligations prevented a drain on individual financial resources. Rather than spend all of the inheritance maintaining unproductive family members, the heir could, in the contemporary period, utilize his resources in more financially productive ways such as for savings and investment. […] Finally, the system of inheritance, along with the large-scale migration resulting from population density and land pressures, is one of the internal incentives that accounts for Bamileke success in the nontraditional world”.[2]

Donald L. Horowitz also attributes the economic success of the Bamileke to their inheritance customs, arguing that it encouraged younger sons to seek their own living abroad. He wrote in “Ethnic groups in conflict”: “Primogeniture among the Bamileke and matrilineal inheritance among the Minangkabau of Indonesia have contributed powerfully to the propensity of males from both groups to migrate out of their home region in search of opportunity”.[3]

References[edit]

- Jump up^ Owono, Julie (25 January 2012). “Unspoken history: The last genocide of the 20th century”. Al Jazeera. Retrieved 26 January 2012.

- Jump up^ A.I.D. Evaluation Special Study No. 15 THE PRIVATE SECTOR: – Individual Initiative, And Economic Growth In An African Plural Society The Bamileke Of Cameroonhttp://pdf.usaid.gov/pdf_docs/pnaal016.pdf

- Jump up^ http://books.google.es/books?id=Q82saX1HVQYC&pg=PA155&lpg=PA155&dq=%22Primogeniture%22+%22Bamileke%22&source=bl&ots=JMOOcssnc-&sig=BtkVUJrmKPp6ZW48t5fyMx_X4Ak&hl=es&sa=X&ei=UgeLUuChHMSv7AbwnYCYBw&ved=0CEQQ6AEwAg#v=onepage&q=%22Primogeniture%22%20%22Bamileke%22&f=false

- Toukam, Dieudonné (2010), Histoire et anthropologie du peuple bamiléké, Paris: l’Harmattan, 2010, 242p.

- Toukam, Dieudonné (2008), Parlons bamiléké. Langue et culture de Bafoussam, Paris: L’Harmattan, 255p.

- Fanso, V.G. (1989) Cameroon History for Secondary Schools and Colleges, Vol. 1: From Prehistoric Times to the Nineteenth Century. Hong Kong: Macmillan Education Ltd, 1989.

- Neba, Aaron, Ph.D. (1999) Modern Geography of the Republic of Cameroon, 3rd ed. Bamenda: Neba Publishers, 1999.

- Ngoh, Victor Julius (1996) History of Cameroon Since 1800. Limbé: Presbook, 1996.

Further reading[edit]

- Knöpfli, Hans (1997—2002) Crafts and Technologies: Some Traditional Craftsmen and Women of the Western Grassfields of Cameroon. 4 vols. Basel, Switzerland: Basel Mission.

External links[edit]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Bamileke. |

http://www.shavei.org/category/communities/other_communities/africa/cameroon/?lang=en

Cameroon

There are some who believe that an ancient Jewish presence may have at one time existed in Cameroon via merchants who arrived from Egypt for trade. According to these accounts, the early communities in Cameroon observed rituals such as separation of dairy and meat products, as well as wearingtefillin.

There are also claims that Jews migrated into Cameroon much later, after being forced southward due to the Islamic conquests of North Africa.

The main claims of a Jewish presence in Cameroon are made by Rabbi Yisrael Oriel, formerly known as Bodol Ngimbus-Ngimbus. He was born into the Ba-Saa tribe; the word “Ba-Saa,” he says, is from the Hebrew for “on a journey.” Oriel also claims to be a Levite descended from Moses.

According to Oriel in 1920 there were 400,000 “Israelites” in Cameroon, but by 1962 the number had decreased to 167,000 due to conversions to Christianity and Islam. He admitted that these tribes had not been accepted according to Jewish law, although he claimed that he could still prove their Jewish status from medieval rabbinic sources.

A website called “Jewish Cameroon” provides more details. Oriel describes the period between 1920 and 1962 as “a ‘spiritual Shoah.’ Because of intense missionary activity, it was like the Soviet Union where Jews had no permission for Jewish education, no batei din (Jewish courts), synagogues or sifrei (books of the) Torah. Everything was taught by oral tradition, Oriel says.”

Oriel’s father, the website continues, Hassid Peniel Moshe Shlomo (Ngimbus Nemb Yemba) was a textile manufacturer, scribe, mohel (ritual circumciser) and tribal leader. Oriel says his father was imprisoned 50 times for teaching his traditional Jewish beliefs. In 1932 he ran away from a Catholic school because they had wanted him to train for the priesthood.

Oriel’s grandfather reportedly built a synagogue in Cameroon, but that it is now in ruins. Oriel’s grandfather is said to have been the last gabbai of the synagogue.

Oriel’s mother, who he calls Orah Leah (her given name was Ngo Ngog Lum), had a large kitchen in which milk and meat were separated – by six meters, he says. Shortly before his mother died in 1957, she told him: “My beloved child, one day you will go to ‘Yesulmi’.” It was not till 1980 that he realized that she must have meant Jerusalem.

Oriel left Cameroon in the early 1960s after the country received independence. He studied law and international relations in France.

Oriel formally converted to Judaism some 20 years and was ordained as a rabbi in Israel, to which he made aliyah and where he lived briefly. He now resides in London and prays at the Persian Hebrew congregation and the Moroccan “Hida” Synagogue and Bekt Midrash on East Bank, Stamford Hill, London. You can see a photo of Oriel here.

Oriel remains active in trying to bring Judaism to Cameroon, as well as neighboring Nigeria, and to bring what he claims are “the 10 lost tribes” back to the fold. There is much more about Oriel on the Jewish Cameroonsite, including some more outlandish claims and grievances Oriel has against the established Jewish community.

Other reported Jewish tribes in Cameroon are said to include Haussa, descended from the tribe of Issachar, who were forced to convert to Islam in the eighth and ninth centuries, and the Bamileke who are largely Christian today. Nchinda Gideon claims that these early immigrants built synagogues but there are no records of them in Cameroon today.

American actor Yaphet Kotto, whose parents emigrated from Cameroon to the United States, claims Jewish descent. Kotto, who died in 2008, had a starring role in the television series Homicide: Life on the Streetand also appeared in films such as Alien and the James Bond movie Live and Let Die.

In his autobiography entitled Royalty, Kotto writes that his father was “the crown prince of Cameroon” and that he was an observant Jew who spoke Hebrew. Kotto’s mother reportedly converted to Judaism before marrying his father. Kotto also says that his great-grandfather, King Alexander Bell, ruled the Douala region of Cameroon in the late 19th century and was also a practicing Jew.

Kotto says that his paternal family originated from Israel and migrated to Egypt and then Cameroon, and have been African Jews for many generations. Kotto writes that being black and Jewish gave other children even more reason to pick on him growing up in New York City. He says that he went to synagogue and occasionally wore a yarmulke when he was younger.

A very tenuous, primarily linguistic connection between Cameroon and ancient Israel can be found through another tribe known as the Bankon who live in the Littoral region of Cameroon. The word “Ban” – also pronounced “Kon” – means “son of prince” in Assyrian, an Aramaic dialect. In her work The Negro-African Languages, a French scholar, Lilias Homburger, points out that the Bankon’s language is “Kum” which may derive from the Hebrew for “arise” or “get up!” Further, the Assyrians called the House of Israel by the name of Kumri.

More recent Jewish presence in Cameroon

Twelve years ago, 1,000 Evangelical Christians in Cameroon decided they no longer wanted to practice Christianity and turned instead to Judaism, embracingpractices from the bible. Their informal conversion to Judaism is similar to Uganda’sAbuyadaya Jewish community which, in 1919, also moved towards Judaism even though, in both cases, they had never met any Jews and had no in-person guidance or mentoring in developing their Jewish identity. The Cameroon community calls itself Beth Yeshourun and is very small, with only 60 members in total.

Much of what the community has learned has been via the Internet, including downloading prayers and songs. Some of the community has taught itself Hebrew; others pray in a mixture of French and transliterated Hebrew.

Rabbis Bonita and Gerald Sussman visited the community in 2010. Their description is presented in detail on the Kulanu website. Here are a few highlights from that trip.

- The Sussmans chose to trust the community’s level of kashrut, eating primarily fish and vegetables.

- Community members washed their hands ritually before eating bread and a meal.

- The community was fairly knowledgeable about Jewish tradition and asked the Sussman’s many questions about Jewish law, such as what to eat at a family event that is not kosher, when do you pray the Minchaafternoon service when you are traveling, and must you stand during the Amidah prayers if you are sick?

- The Shabbat service, held in the Beth Yeshourun synagogue, was remarkable similar to today’s mainstream Orthodox Judaism, including the full Kabbalat Shabbat, the singing of Lecha Dodi and even the closing Yigdal prayer.

- On Shabbat day, the community sang a mixture of songs in the local language as well as modern Israeli songs such as Jerusalem of Gold.

- The community prays three times a day and holds Torah study sessions twice a week, using material gleaned from the web.

- The community has created its own siddur (prayer book) of 150 pages, also by downloading content from the Internet.

77.82% (West African) Yoruba

8.11% (Middle East) Jewish, Palestinian, Bedouin, Bedouin South, Druze

14.07% (Europe) Finnish and Russian

NOTE: This test is an autosomal test and this test will go back 6-8 generations, which is about 200 years ago.

Also FTDNA list geographically Sudan and Egypt as part of the Middle East, although the countries of North Africa, which has Indigenous Nubians and Bedouins as well as an influx of Arab and Middle Eastern populations.

My middle eastern descent groups Levante share with the Druze, who are a monotheistic religious community, found primarily in Syria, Lebanon, Israel and Jordan, which emerged during the 11th century from Ismailism. The Druze people reside primarily in Syria, Lebanon and Israel. which is home to about 20,000 Druze.

The Institute of Druze Studies estimates that 40% -50% of Druze live in Syria, 30% to 40% in Lebanon, 6% -7% in Israel, and 1% to 2% in Jordan.

Large communities of expatriate Druze also live outside the Middle East in Australia, Canada, Europe, Latin America and West Africa. They use the Arabic language and follow a social pattern very similar to the other peoples of the eastern Mediterranean region.

Family Locator My ancestry is shared by both parents and grandparents and Great Great on both sides.

This test should not be confused with a Test of ancestral origin, as mtDNA and Y-chromosome test.

My autosomal:

214,911 autosomal-it-results.csv

More likely adjustment of 24.9% (+ – 14.4%) Africa (subcontinents various)

and 58.2% (+ – 15.3%) Africa (all West African)

that is 83.1%, total Africa

and 16.9% (+ – 1.2%) Europe (various sub-continents)

The following are possible population sets and their fractions,

probably on top

Mandenka Bantu Ke = 0.439 = 0.382 = 0.179 or Russian

Maasai = 0.152 Yoruba = 0.671 = 0.177 or Russian

The Ethiopian-= 0.129 = 0.711 = 0.160 Finland Yoruba or

The Ethiopian-Yoruba = 0.129 = 0.710 = 0.161 or Russian

Bantu Ke = 0.431 = 0.391 = 0.178 Mandenka or Finland

Maasai = 0.149 Yoruba = 0.675 = 0.176 Finland or

The Ethiopian-Yoruba = 0.116 = 0.734 = 0.150 Finland or

Mandenka Bantu Ke = 0.396 = 0.424 = 0.180 or Irish

T-Ethiopian Yoruba = 0.115 = 0.734 = 0.151 Finland or

Mandenka Bantu Ke = 0.433 = 0.389 = 0.178 Belarus

Western Europe, but it is also very possible.

3.2% Native American (European subtracts).

but in fact the European is probably British. And there

Native American 3.0% of unknown type. This is typical

African-(Euro) American.

Doug McDonald

A custom fit is better than automatic:

214,911 autosomal-it-results.csv

Irish 0.1461 0.0259 0.7159 0.1122 Maya Yoruba The Ethiopian-or

Irish 0.1467 0.0256 0.7156 Na-Dene The Yoruba-Ethiopian or 0.1120

English 0.1431 0.0279 0.7146 0.1144 Maya Yoruba The Ethiopian-or

English 0.1435 0.0280 0.7143 Na-Dene The Yoruba-Ethiopian or 0.1142

Irish 0.1897 0.0255 0.1091 0.6758 Yoruba Maya Mandenka

French or Spanish is also possible, in the same amount, with the same probability.

The Oromo-Ethiopians stands for, but this is probably not real: it just means that the

African is somewhere bewteen part of Nigeria and Ethiopia., Very nearest Nigeria.

The Middle East (violet) on chromosomes comes from East Africa, they

are mixed with people of Arabia.

The American general in the U.S.. The red spot (euro) in teh map

is in the wrong place.

Doug McDonald

There are not many studies on my Y-DNA Haplogroup E1b1a7a this time, but these references should be helpful ..

References:

Y-chromosomal variation: Insights in the history of Niger-Congo groups:

http://mbe.oxfordjournals.org/content/early/2010/11/25/molbev.msq312.abstract

Y-DNA haplogroup E1b1a in Wikipedia:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Haplogroup_E1b1a_ (Y-DNA)

Popular Yorubua:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Yoruba_people

The Druze People:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Druze

The Yoruba list SNP was inferred from the presentation of dbSNP

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/SNP/snp_viewBatch.cgi?sbid=856991

my father and my son on lap

CurtirCurtido por 2 pessoas

Perfect

CurtirCurtido por 1 pessoa

Very interesting…i like this narrative. We also share the same Y-haplogroup E1b1a7a (U174). My cousin tested for a male line that I couldn’t test for via AfricanAncestry (patriclan). His results were that he share ancestry with the Bamileke as well (his Y hapgroup is also E1b1a7a too). Mine was Makua of Mozambique – though I’m not quite convinced with AfricanAncestry’s testing methods especially since it uses such few markers (low resolution). Be that as it may, I still admire how you’ve set-up this page. Great Job!

CurtirCurtido por 1 pessoa

Thats wonderful ! Thank you, you are welcome!

CurtirCurtido por 1 pessoa

But just so that I’m clear, African Ancestry using only 8 markers is actually problematic. At least FTDNA, starts at 12 markers and i have over 40 matches, most from Saudi Arabia. So, i personally take African Ancestry Patriclan test with a VERY TINY grain of salt. It’s not that reliable. However, i still think its a viable service (mainly the Matriclan test) for African descendants in the Diaspora.

CurtirCurtido por 1 pessoa

thank you very much for the comment, africanaancestry was right about the Bamileke tribe, my Brazilian family already said about it

CurtirCurtido por 1 pessoa

Bom dia irmão E.C. Rand;

Haplogrupo paterno

Você descende de uma longa linhagem de homens que pode ser rastreada até o leste da África há mais de 275.000 anos. Estes são os homens de sua linha paterna, e seu haplogrupo paterno lança luz sobre a história deles.

Resumo

Detalhes Científicos

ANTONIO, seu haplogrupo paterno é E-P252.

À medida que nossos ancestrais se aventuraram para fora da África oriental, eles se ramificaram em diversos grupos que cruzaram e recruzaram o globo ao longo de dezenas de milhares de anos. Algumas de suas migrações podem ser rastreadas por meio de haplogrupos, famílias de linhagens que descendem de um ancestral comum. Seu haplogrupo paterno pode revelar o caminho percorrido pelos homens de sua linha paterna.

Migrações de sua linha paterna

Haplogrupo A 275.000 anos atrás

As histórias de todas as nossas linhagens paternas remontam a mais de 275.000 anos até um único homem: o ancestral comum do haplogrupo A. As evidências atuais sugerem que ele era um dos milhares de homens que viviam na África oriental na época. No entanto, enquanto seus descendentes de linha masculina transmitiam seus cromossomos Y geração após geração, as linhagens dos outros homens morreram. Com o tempo, somente sua linhagem deu origem a todos os outros haplogrupos que existem hoje.

E-M180

17.000

Anos atrás

Origem e migrações do haplogrupo E-M180

Sua linha paterna origina-se do ramo E-M180 de E, que domina o sul do Saara. O haplogrupo se originou há cerca de 17.000 anos nos bolsões da África ocidental que eram habitáveis na época, quando grande parte do continente era extremamente seco devido às condições climáticas da Idade do Gelo. Mais de dez mil anos depois, os homens portadores do haplogrupo E-M180 migraram para o sub -África do Saara, impulsionada pelo desenvolvimento da agricultura e da siderurgia na região.

E-M180 é mais comum hoje em dia entre falantes de línguas Bantu e aqueles relacionados a elas; atinge níveis de até 90% entre os mandinkas e iorubás da África ocidental, onde começaram as migrações. Mais longe de sua origem, o E-M180 atinge frequências de 50% ou mais nos Hutu, Sukuma, Herero e! Xhosa. A linhagem também é o haplogrupo mais comum entre os indivíduos afro-americanos do sexo masculino. Cerca de 60% dos homens afro-americanos caem neste haplogrupo principalmente devido ao comércio de escravos no Atlântico, que atraiu indivíduos da África Ocidental e de Moçambique, onde E-M180 representa a maioria dos homens.

E-P252

12.000

Anos atrás

Seu haplogrupo paterno, E-P252, remonta a um homem que viveu há aproximadamente 12.000 anos.

Isso foi há quase 480 gerações! O que aconteceu entre então e agora? À medida que pesquisadores e cientistas cidadãos descobrem mais sobre seu haplogrupo, novos detalhes podem ser adicionados à história de sua linhagem paterna.

E-P252

Hoje

E-P252 é relativamente comum entre os clientes 23andMe.

Hoje, você compartilha seu haplogrupo com todos os homens que são descendentes de linha paterna do ancestral comum do E-P252, incluindo outros clientes da 23andMe.

1 em 120

Os clientes 23andMe compartilham sua atribuição de haplogrupo.

Você compartilha uma antiga linhagem paterna com o Faraó Ramsés III.

E-V38

O Faraó Ramsés III defendeu o Egito em três guerras consecutivas durante seu reinado de aproximadamente 30 anos, mas provocou dissensão dentro de sua administração. Catalisada por conflitos internos crescentes, uma das esposas menores de Ramsés, Tiye, traçou um complô para que seu filho, Pentawer, usurpasse o trono ao mandar assassinar Ramsés III junto com seu herdeiro designado. Um registro de papiro do julgamento resultante explica que a trama falhou e que todos os envolvidos foram julgados e condenados.

No entanto, uma tomografia computadorizada moderna da múmia de Ramsés III revelou um corte profundo em sua garganta, reabrindo um caso que há muito se pensava encerrado. Os embalsamadores fizeram de tudo para encobrir outras feridas, incluindo fazer um dedão falso de resina onde o verdadeiro de Ramsés havia sido decepado, provavelmente durante um ataque fatal. Por milhares de anos, os adornos do enterro de Ramsés esconderam as feridas que marcam um dos dramas reais mais famosos da história. A linhagem paterna de Ramsés III pertence ao haplogrupo E-V38, do qual sua linha também se origina. Você e Ramsés III compartilham um ancestral ancestral de linha paterna que provavelmente viveu no norte da África ou no oeste da Ásia.

A genética dos haplogrupos paternos

O cromossomo Y

A maior parte do DNA do seu corpo é agrupada em 23 pares de cromossomos. Os primeiros 22 pares são iguais, o que significa que eles contêm aproximadamente o mesmo DNA herdado de ambos os pais. O 23º par é diferente porque nos homens, o par não combina. Os cromossomos desse par são conhecidos como cromossomos “sexuais” e têm nomes diferentes: X e Y. Normalmente, as mulheres têm dois cromossomos X e os homens um X e um Y.

Seu sexo genético é determinado por qual cromossomo sexual você herdou de seu pai. Se você é geneticamente masculino, recebeu uma cópia do cromossomo Y de seu pai junto com um gene conhecido como SRY (abreviação de região Y determinante do sexo ), importante para o desenvolvimento sexual masculino. Se você é geneticamente feminino, recebeu uma cópia do cromossomo X de ambos os pais.

Os haplogrupos paternos são determinados pelo cromossomo Y. Os homens têm um cromossomo X e um cromossomo Y. O cromossomo Y contém o gene SRY, que determina o sexo masculino. As mulheres têm dois cromossomos X e nenhum cromossomo Y.

Faça mais com os resultados do haplogrupo.

Responder à pesquisa

Contribua com a pesquisa e nos ajude a compreender os padrões de variação genética em todo o mundo.

Trace sua linha paterna

Visite DNA Parentes para identificar parentes que podem estar em sua linha paterna.

23andMe, Inc.

Dê o presente da descoberta do DNA.

Ganhe até $ 20 para cada amigo que você indicar.

ANCESTRALIDADE

Visão Geral de Ancestrais

Todos os relatórios de ancestralidade

Composição de Ancestrais

Parentes de DNA

Peça o seu livro de DNA

SAÚDE E TRAÇOS

Visão geral de saúde e traços

Todos os relatórios de saúde e características

Meu Plano de Ação de Saúde

Predisposição para a saúde

Status da operadora

Bem estar

Características

PESQUISAR

Visão geral da pesquisa

Pesquisas e estudos

Editar Respostas

Publicações

AMIGOS DA FAMÍLIA

Ver todos os parentes de DNA

Árvore genealógica

Suas Conexões

GrandTree

Comparação Avançada de DNA

© 2021 23andMe, Inc.

Termos de serviço

Termos de adesão

Declaração de privacidade

CurtirCurtido por 1 pessoa

Republicou isso em Black History & Culture.

CurtirCurtido por 1 pessoa

Mr. Antonio Florentino, I would like to extend to you an invitation to a Bamileke festival in NJ, in the US in you can make it. Please contact me at infoyembaus@gmail.com for further details

CurtirCurtido por 1 pessoa